Èzili Dantò’s note: Haiti deforestation lie

Èzili Dantò’s note: Haiti deforestation lie

Haiti finally got one unbias and good news report. The information shared in the Vice News article (copied below) titled, “One of the most repeated facts about Haiti is a lie” by M.R. O’Connor, vindicates our work (here, here) and it feels so good.

O’Connor’s article is about geologist Peter Wampler’s deforestation research in Haiti.

O’Connor’s article is about geologist Peter Wampler’s deforestation research in Haiti.

“Wampler had debunked the myth of how many trees were in Haiti, but his findings, published in the International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation in 2014, didn’t gain much traction among environmentalists or development agencies.”

O’Connor writes further, that:

“Haiti’s reputation as a deforested wasteland is based on myth more than fact — an example of how conservation and environmental agendas, often assumed to be rooted in science, can become entangled with narratives about race and culture that the powerful tell about the third world.”

Except for the end of the article, when O’Connor brings up Sean Penn’s interventions in Haiti in a positive (or at best, a neutral) light, this is one of the best information recently written by a non-Haitian. It touches the tip of the iceberg on the often repeated lies about Haiti. But it’s the sort of information that helps fight the powerful poverty pimping charitable industry, the NGOs, Bretton Woods organizations, the US occupation behind UN proxy guns and the embedded media’s imperial agenda in Haiti. It’s good to know the actual percentage of Haiti forest cover and not the false stereotypes, dire images and stigmatization.

O’Connor writes that Professor Wampler found:

Haiti’s forest cover was more than 32 percent, “a number similar to the coverage in the United States, France, and Germany, and far higher than in Ireland and England.“

Baladères Haiti, still under water, two weeks

after Hurricane Matthew disaster.

How do you want people not to get cholera from

this? Aye! The government should evacuate them.

***

MEDIA SILENT as tens of thousands of Black people march against Hillary Clinton around the country. Protestors chant: “Don’t vote for Hillary, she’s killing Black people.” See also, Facebook post comments ;

Haiti Message to Donald Trump and

Let Establishment Democrats Scream But Haitian and Haitian-American Disgust with Clintons Is Justified.

***

Donate to support the Hurricane Matthew victims

with Zili Dlo Clean Water Renewable Energy

Geologist Peter Wampler’s nearly 10-year research debunks the often repeated lie that Haiti had as little as 2 percent tree cover because Haitians cut down wood to burn for charcoal. We are grateful to Wampler and the others mentioned in the article for persevering against the NGO establishment and to journalist O’Connor for covering this and exposing this lie in detail and telling the inconvenient truth. Other researchers have also “reached similar conclusions of unconventionally high arboreal coverage in contemporary Haiti.”

There are other often repeated lies about Haiti which are sold as fact. And, we’ve been outlining them for years to demand an end to the Western plunder that hides behind the constant disaster stories. The exaggerations service Western extraction companies, colonial interests and the crisis caravan of the Clinton-Paul Farmer charitable industrial complex.

“I heard that 2 percent number quoted everywhere…All the news outlets had this narrative that it’s the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and has 2 percent forest cover. But I’d been to these mountainous areas and seen forest cover that was more than 2 percent. I could see it with my own eyes” — Peter Wampler, US geologist

Hurricane Matthew shows the devastated South of Haiti was a green land hardly ever photographed by the poverty pimps for their newspaper stories when it was green. Pic Macaya National Forest in Haiti, an international biosphere reserve, doesn’t exist for the racist minions of Western imperialism and the Wall Street pirates and plunderers in Haiti.

But the veil is lifting.

Soon, we will read a major feature about how Haiti has less violence than the Dominican Republic, in fact, than most nations in the Western Hemisphere. Soon, we will read how the US built its largest Embassy in the Western Hemisphere in Haiti because of Haiti’s massive wealth and riches. Soon, we will read how the Eurocentric lies and racist, often repeated facts about Haiti violence, corruption, deforestation and innate poverty are tools used to make the country an ATM for the charitable industrial complex and to continue the Western occupation and colonial control by the three colonial powers at the UN Security Council.

One day soon, Haiti’s informal economy and the over 172,000 Haiti Lakou yo – communally owned family plots of lands, worked by our small farmers and market women, will count towards valuing Haiti’s real wealth. One day soon, the eugenicist West, depopulating Haiti and Africa with perpetual war, destabilization, regime changes, fake elections, dictatorship, fake aid, foul inoculations, drugs, diseases, free trade that promotes famine and weather warfare, will face more honest journalists, researchers and their own awaken people’s outrage.

“A USAID spokesperson who was aware of Wampler’s study agreed that the correct figure for tree cover is likely between 32 and 40 percent but defended the 2 percent statistic as referring to “original forest cover,” meaning before European contact.” (See also Haiti is Covered With Trees by Andrew Tarter, envirosociety.org, May 19, 2016 where facile excuses are made for the Internationals’ perception management narrative that historically defames the Black population, exaggerates Haiti low tree cover to feed the colonist.)

The racist imperial West works overtime to repeat lies about Haiti to dominate, exterminate Haitians, move them off their fertile lands to expropriate Black Haiti’s natural and human resources.

O’Connor’s findings show how the Internationals keep Haiti in a choke-hold; deliberately push images of Haiti devastation to simultaneously demoralize, discourage, make Haitians dependent to raise more monies for the foreign do-gooders. The article is a breath fresh air in a sea of Eurocentric lies about Haiti. The Hillary and Bill Clinton and Paul Farmer poverty pimps are getting exposed by more and more people than just us at Èzili’s HLLN and the tireless Haiti grassroots resistance to tyranny who battle the vampires and their local ghouls at home and from abroad.

Eight years ago, to help combat the false stereotypes blaming deforestation on the myth of Haiti overpopulation and the Haitian peasant lifestyle and culture for the purported deforestation, I pointed out in Ezili’s HLLN Counter-Colonial Narrative on Deforestation, that:

“Environmental Minister Jean-Marie Claude Germain indicated in an AP article titled Haiti’s Efforts to Save Trees Falters, that “reforestation projects and efforts to preserve trees in three protected zones were set back by the violent rebellion that ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004 and prompted the U.N. to send in thousands of peacekeepers to restore order. Even though there were agricultural laws, the laws were not respected.“

What’s unique and different about Wampler is that most white people go to Haiti, see the lies with their own eyes, but don’t expose it when they return home. Instead, they join in with the poverty pimps to raise monies off the lies. Sean Penn is one of those white boys who became an instant Haiti expert after a few months in Haiti. He saw Haiti was less violent compared to the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Bahamas, to name a few; had a front row seat during the Clinton-OAS rigged Martelly elections; eyeballed Haiti’s relative forest cover, but remained silent.

In fact, he used his celebrity status to distract attention from the Clinton crimes, get monies for his organizations from the Red Cross meant for Haitians and turned a blind eye to the lawless Martelly regime put in by the Clintons under the Obama Administration. With other useful idiots from Hollywood and the so-called “Liberal” sector, Sean Penn accepted the Clintons’ pay-to-play was normal, drinking champagne with them to celebrate “progress for Haiti” by inaugurating a sweatshop as the height of Haiti earthquake recovery. These folks said nothing as the UN shot unarmed Haitians dead in the streets who protested the US occupation behind UN guns, fake elections, cholera democracy and fake aid. But they want to save the trees? The colonial truth doesn’t raise funds, but keeping Haiti in a choke-hold, lying about even our trees is profitable.

The worst Haiti suffers, or is made out to be, the more funds the “hero/philanthropist” raises. 32% forest cover is 2% forest cover in their Avatar script.

Colonial celebritism, along with the white man’s burden narrative, services the Lone Ranger, Tarzan, Superman, their Tonto and Jane sidekicks. It’s not real. Reality manipulated. But in the Discoverers’ world, the natives play the part of the savages, killing what in Haiti? oh yeah, nature and the trees?

Wasn’t it the Discoverers who clear cut the forests of Haiti to build French palaces and cathedrals centuries ago? Aren’t the white savior nations continuing the environmental apocalypse in other ways to this day? Digging up Haiti for construction aggregate, marble, coal and planning open-pit gold mining in the time of US-introduced cholera?

Wasn’t it Haitian spiritual relationship with trees, mountains, lakes, ancestral lands and souls the reason for the brutal 1941 US Rejete program? The US wanted to disconnect the Vodouist from their Ancestral and nature worship. The revered Mapou and other trees were burned to stop Haitian care for natural portals and high vibration habitats revered by the Vodouist. Thousands of acres of peasant lands were cleared of sacred trees so that the US could take the land for big US agribusiness and for the unsuccessful try to make Haiti a Western-controlled rubber kingdom where it would grow sisal or rubber trees (for portable bridges, the tires in military jeeps, planes, aircraft guns, to name a few uses.)

“During the Duvalier era, it was an American company that simply and without conscience or remorse clear cut major portions of the dense pine forest – Forêt des Pins – in Thiote, Haiti, a forest of centuries old, if not thousand-year-old giant pine trees, and took Haiti’s precious lumber to the US.” — Ezili’s HLLN Counter-Colonial Narrative on Deforestation (See also, HLLN on the causes of Haiti deforestation and poverty.)

More recently, Haitians know that the US corporatocracy has taken down whole mountains these last 30 years. They export out the healing soil, high-grade limestone, lignite, coal, construction aggregate, marble, chalk, Haiti gemstones and other precious minerals found within. But the “Haiti experts” do not calibrate these factors. Nonetheless, 75 years after that scorched earth US Rejete policy in Haiti, O’Connor writes:

“Haiti’s practice of carefully managed woodlots known as rakbwa, in which trees are grown, culled and sold for construction or charcoal, have played a role in sustaining the country’s tree cover. Tarter, the anthropologist in Haiti, told me that rakbwas have been in use for nearly two centuries…Andrew Tarter, an expert on the history of Haiti’s economic and spiritual relationship to trees, told me from his home in Port-au-Prince”

A decade ago, Èzili’s HLLN made it clear that Haiti’s poverty and deforestation results from the theft and exploitation of Haiti by the world’s wealthy countries and their corporations. Wampler had a difficult time getting the Establishment to tell the truth and to stop blaming deforestation on Black people. But that’s part and parcel of what Establishment tyranny is about; what Haitians go through. But a thousand times worst since our agency is destroyed by colonialism. We are not the observers and witnesses but the objects of empire’s wrath and the subjects of fieldwork.

Èzili Dantò

Haitian Lawyers Leadership Network

October 2016

The world’s favorite disaster story

One of the most repeated facts about Haiti is a lie

By M.R. O’Connor on Oct 13, 2016

Original Source: Vice News

Deforestation Myth in Haiti. Source: Vice News article by M.R. O’Connor

When the geologist Peter Wampler first went to Haiti, in 2007, he didn’t expect to see many trees. He had heard that the country had as little as 2 percent tree cover, a problem that exacerbated drought, flooding and erosion. As a specialist in groundwater issues, Wampler knew that deforestation also contributed to poor water quality; trees help to lock in rich topsoil and act as a purifying filter, especially important in a country where about half of rural people do not have access to clean drinking water.

Haiti is frequently cited by the media, foreign governments and NGOs as one of the worst cases of deforestation in the world. Journalists describe the Caribbean nation’s landscape as “a moonscape,” “ravaged,” “naked,” “stripped” and “a man-made ecological disaster.” Deforestation has been relentlessly linked to Haiti’s entrenched poverty and political instability. David Brooks, the conservative New York Times columnist, once cited Haiti’s lack of trees as proof of a “complex web of progress-resistant cultural influences.” More recently, a Weather Channel meteorologist reporting on the advance of Hurricane Matthew made the absurd claim that Haiti’s deforestation was partly due to children eating the trees.

Few places in the world have as dismal a reputation. And as the recent destruction wrought by Hurricane Matthew shows, Haiti is tragically vulnerable to natural disasters. But as Wampler would discover, Haiti’s reputation as a deforested wasteland is based on myth more than fact — an example of how conservation and environmental agendas, often assumed to be rooted in science, can become entangled with narratives about race and culture that the powerful tell about the third world.

Over the next five years, as Wampler crisscrossed the country for his research, he began to undergo a cognitive dissonance. “I heard that 2 percent number quoted everywhere,” he said. “All the news outlets had this narrative that it’s the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and has 2 percent forest cover. But I’d been to these mountainous areas and seen forest cover that was more than 2 percent. I could see it with my own eyes.”

Satellite Photo Showing Haiti Deforestation Lie – Source: Vice News

He began searching for the original source of the forest-cover statistic. To his surprise, he couldn’t find one. The few citations he discovered in scientific studies couldn’t be substantiated. Some scientific and development literature used a 4 percent estimate that came from the Food and Agriculture Organization, a United Nations agency. That number also struck him as too low.

Wampler, a professor at Michigan’s Grand Valley State University, uses geographic information systems and satellite imagery frequently in his work, and he decided to employ them to satisfy his curiosity about the trees in Haiti. He enlisted several students and began gathering high-resolution imagery of the island from LandSat, the database operated by the United States Geological Survey. Stitching together images from 2010 and 2011, he formed a mosaic that covered the entire country. He combined the images in three wavelengths to highlight vegetation and then trained a computer to spot trees in the images. To check the accuracy, he manually compared the computer’s automated analysis to random samples chosen from Google Earth.

When the results came back, his first thought was that he had to do the whole process again. “Let’s check this 10 times to make sure it’s right,” he told his colleagues. According to their analysis, Haiti’s forest cover was more than 32 percent.

Wampler wondered whether they had set a sufficient minimum area for tree cover. So they used the FAO’s definition of a “forest,” which includes trees higher than 5 meters (about 16 feet) covering at least half a hectare. He ran the analysis again. The computer estimated Haiti’s forest coverage at nearly 30 percent, a number similar to the coverage in the United States, France, and Germany, and far higher than in Ireland and England. Wampler had discovered a rarity in today’s world: a good-news environmental story in one of the planet’s poorest countries. But then he had a troubling thought: “People won’t like this.”

“It doesn’t fit the narrative” that poverty causes deforestation and deforestation exacerbates poverty, he said. Foreign governments, charities, development banks, and the foreign media tend to present this relationship as an indisputable fact. “Organizations use this statistic as a lever to get funding and help. For them, it’s a lot more convenient to have a narrative that works.”

He had discovered a rarity in today’s world: a good-news environmental story in one of the planet’s poorest countries. But then he had a troubling thought: “People won’t like this.”

Environmentalists and development experts have drawn a connection between overpopulation, ecological devastation and poverty for decades. “The narrative about overpopulation — and deforestation is usually not far behind — is what’s called a blueprint narrative,” said Jade Sasser, a professor of gender and sexuality studies at the University of California, Riverside. “It gets applied in a variety of different development settings regardless of local history and situations.” Blueprint narratives, first described by policy analyst Emery Roe in 1991, proffer ready-made diagnoses of environmental problems — overgrazing by cattle in Africa leads to desertification, for instance — but the solutions are often unsuited to local contexts and conditions.

Such narratives can also dehumanize. One area of Sasser’s research looks at how Western NGOs portray the poor, often communities of color, as environmentally unaware and in need of outside intervention. In reality, she said, local communities often use “nature” in ways that just don’t fit the notions of pristine wilderness at the heart of many conservation policies.

Paul Robbins, a political ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, called the environmental movement’s blaming of the poor for deforestation an “obsession” that is both “ironic” and “empirically questionable.” In West Africa, for example, the idea that local communities have caused deforestation is orthodoxy among development and environmental policymakers, but analysis of historical data and first-person accounts rarely support it.

Wampler had debunked the myth of how many trees were in Haiti, but his findings, published in the International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation in 2014, didn’t gain much traction among environmentalists or development agencies. The World Bank, USAID, Oxfam America and multiple United Nations agencies still cite a stat of 1 to 4 percent for forest cover in Haiti. (A USAID spokesperson who was aware of Wampler’s study agreed that the correct figure for tree cover is likely between 32 and 40 percent but defended the 2 percent statistic as referring to “original forest cover,” meaning before European contact.)

“It’s been controversial in some circles,” Wampler said. “Some people don’t want to talk about it. It’s not the story that they want to tell about Haiti.”

***

For centuries, outsiders predicted the failure of the world’s first country founded by rebel slaves, and for decades outsiders have forecast an environmental collapse rooted in the cultural failures of those slaves’ descendants. Wampler’s study hinted at a different, more interesting story, one of a resource-challenged people who created a unique relationship with their trees through adaptation and management.

The study hinted at a different, more interesting story, one of a resource-challenged people who created have a unique relationship with their trees through adaptation and management.

Many narratives about Haiti, according to anthropologist Gina Athena Ulysse, are uninformed and ahistorical. Even after the catastrophic earthquake in 2010, which brought yet another influx of foreigners to document Haiti’s tragedies, the media’s representations — of an overpopulated country of irrational, progress-resistant and ignorant people — could be traced back to those popular in the 19th century, after Haiti’s slaves launched a rebellion and won their independence from France. Rather than applaud this landmark in the history of human freedom, governments around the world viewed the successful slave insurrection with horror. This was 60 years before the United States’ Civil War, and the Republic of Haiti challenged the international system of colonization and slavery. The country’s history since is a series of foreign nations imposing crippling debt, invading, occupying and intervening, with often dire consequences for Haiti’s people.

The notion that Haiti’s trees, or lack of trees, was itself a significant problem dates to the aftermath of World War II, when American development agencies arrived on the island looking for projects. Haiti had hardly any old-growth forests, and the culprit, they believed, was overpopulation: Nearly 4 million Haitians, crammed into a tiny portion of the island, had exceeded the environment’s capacity to support them. Desperate for agricultural land and charcoal, Haitians shortsightedly cut down whatever trees they could find, setting into motion a cycle of erosion, diminishing food production, poverty and hunger.

By the late 1970s, USAID was warning of an environmental apocalypse by the turn of the century if the rate of tree cutting by Haiti’s rural poor persisted. Development agencies had launched projects focused on planting new trees and protecting forests from Haitian farmers and charcoal producers, but they had little to show for it.

These early reports of deforestation were based on low-resolution satellite and aerial images and flawed surveys that were likely biased by lack of easy access to rural parts of the country, anthropologist Andrew Tarter, an expert on the history of Haiti’s economic and spiritual relationship to trees, told me from his home in Port-au-Prince. Researchers “rented cars, so they went to places they could get to in a car,” he said. “Well, those are the same places where [wood and charcoal] trucks can get to and [they] were highly denuded.”

Tarter described the dissemination of dire deforestation statistics as a game of telephone spanning decades, in which incomplete information was used to simplify complex environmental and socioeconomic issues. But it also spread because “the world is addicted to apocalyptic stories,” he said, and Haiti is one of the world’s favorite disaster stories.

The world is addicted to apocalyptic stories, and Haiti is one of the world’s favorite disaster stories.

One critical link in the chain of dissemination was a National Geographic article about Haiti published in 1987. The writer, Charles Cobb, described a country in deep despair, afflicted by political corruption, violence, overpopulation, disease and crushing poverty. “Statistics,” he wrote, “do not begin to convey the dimensions of human wretchedness.” Cobb included deforestation among the country’s litany of tragedies, citing the “bygone glory of Haiti’s lush mahogany and tropical oak forests.” “Hungry peasants have stripped the land of its soil-stabilizing tree cover to plant quick-growing foodstuffs,” he wrote.

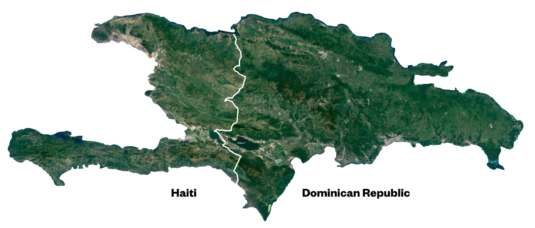

In the middle of the article appeared a photo that would become one of the most iconic and influential images documenting Haiti’s problems. It is an aerial view of the border delineating Haiti and the Dominican Republic; on one side are parched “bare-skinned” mountains and on the other a blanket of verdant forest.

The Eurocentric Spin to Justify White Savior Perpetual Fundraising. This now infamous aerial photograph of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic appeared in National Geographic in 1987. (James P. Blair/National Geographic/Getty Images)

For years, foreign journalists and academics rehashed Cobb’s article. “Haiti on the Brink of Ecocide” was the title of one journal article published in 1994. A decade later, the Associated Press reported that “poverty has transformed Haiti’s once-verdant hills into a moonscape” and “even the mango and avocado trees have started to vanish.” Soon after, the best-selling author and academic Jared Diamond dedicated a chapter of his book “Collapse” to why Dominicans protected their forests while Haitians degraded theirs. The border photo appeared in Al Gore’s 2006 documentary “An Inconvenient Truth.”

Farmers and charcoal producers were blamed for the deforestation throughout the 20th century. But the destruction of the country’s old-growth forest began far earlier with French colonists who cleared the land for slave plantations and used the wood in the sugar-production process. After colonialism, forest laws in many parts of the world as well as the emerging environmental movement borrowed the legal and ideological template of colonialism, explained Robbins, the University of Wisconsin-Madison ecologist, and criminalized poor people’s use of trees.

But evidence that poverty causes deforestation is pretty scarce. “Deforestation and poverty correlate at the regional and national level,” Robbins explained in an email, “but of course, correlation is not causation! Poor places experience forest-cover loss because they are exploited by wealthy places.”

When the French lost their prize colony in 1804, they levied an indemnity on the new Haitian government as punishment. To pay this debt, Haitians began exporting mahogany to France; by 1842 they were sending 4 million cubic feet of it overseas every year. “Much of the deforestation of the precious hardwoods occurred in the 19th century when the Haitian government turned over mahogany forests to outside companies,” said Gerald Murray, an anthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of Florida. “Then it was the outside world — USAID, the World Bank, the United Nations — that later decided deforestation was a problem in Haiti.”

It was the outside world — USAID, the World Bank, the United Nations — that later decided deforestation was a problem in Haiti.

In 1979, USAID hired Murray, who had lived in rural Haiti for years, to find out why the agency’s tree-planting programs weren’t working. Despite 30 years of effort, Haitians didn’t seem interested in planting forests. Murray spent a summer talking to farmers and peasants about trees. The tree-planting programs, he noticed, focused on ecology and, problematically, gave ownership of newly planted trees to the Haitian government, which the peasants distrusted. Murray thought the development agencies, under the influence of environmentalists, had gotten it all wrong. They saw trees as emblems of Mother Nature in need of saving. “It was too late! There were no original forests left,” he said.

Murray’s radical recommendation was that policymakers abandon “the podium and the pulpit” of ecology and saving nature and provide rural families with both seedlings and harvest rights to the trees they grew. He predicted that under those conditions, Haitians would fill the landscape with trees. Over the next two decades, a project funded by USAID and implemented by the Pan American Development Foundation resulted in more than 300,000 Haitian peasant households planting 65 million trees.

Murray continues to visit Haiti each year and was not at all surprised by the results of Peter Wampler’s study, though he said it is unlikely that his project — which planted trees specifically for harvest — is responsible. It’s possible that a third of Haiti had tree cover all along.

It’s more likely that Haiti’s practice of carefully managed woodlots known as rakbwa, in which trees are grown, culled and sold for construction or charcoal, have played a role in sustaining the country’s tree cover. Tarter, the anthropologist in Haiti, told me that rakbwas have been in use for nearly two centuries, and his guess is that Wampler’s finding represents a resurgence of trees. “I suspect that Haiti might have actually been more denuded 30 years ago,” he said. “Trees with deeper taproots are growing up on land that’s been abandoned [as] people are moving out of rural areas into urban areas.”

Green Haitian Landscape -Source: Getty Images

If this turns out to be the case, the implications are amazing. Urbanization usually creates a greater demand for charcoal, because people in cities don’t have easy access to firewood. So it’s possible that over the last 40 years, Haitians not only avoided the environmental apocalypse predicted for them but also expanded their country’s tree cover, even as the population has grown to 10 million people, more of whom live in cities.

Wampler is designing another study to compare present tree-cover levels with archival satellite images from the 1970s to determine whether his earlier results represent a decrease or increase in trees in the last four decades.

Whatever the extent of tree cover, soil erosion, groundwater contamination, and deadly flooding remain significant problems in Haiti. Cultivating treeless, steep mountainsides for agriculture, a common practice, is environmentally damaging and allows topsoil to wash out. Haiti’s tree cover may be around 30 percent, but it is patchy, which affects biodiversity, drought, water quality and the impact of natural disasters like Hurricane Matthew, now estimated to have taken at least a thousand lives. These types of events are only expected to increase with climate change.

“In terms of ecological theory, a small patch of forest is not equal to a forest,” explained Starry Sprenkle-Hypolite, an ecologist in Haiti. People are not ignorant of these issues; they just don’t have the resources to fix them, she explained. “There is a lot of consciousness of the environment and nature and environmental ethics here; it’s a lack of means that is the problem.”

At least one development organization is changing its approach based on the new forest-cover data and a greater understanding of local management practices. J/P Haitian Relief Organization, founded by the actor Sean Penn, is currently raising $300 million in partnership with the Haitian and French governments to enhance Haiti’s climate resiliency. The project, called “Haiti Takes Root,” has launched a study with the World Bank to better understand charcoal production and consumption. “Because it’s illegal and informal and misunderstood, charcoal has been the bogeyman,” said Chris Ward, the project’s executive director. “But it’s the biggest agricultural value chain in the country. We might be able to use that as a driver of reforestation, not deforestation.”

Reforestation may prove simpler than correcting the decades of environmental doomsaying that has contributed to Haiti’s status as the world’s favorite disaster story. But statistics tell much more than a story of wretchedness in Haiti; they also reveal ingenuity.

M.R. O’Connor is a journalist and the author of “Resurrection Science: Conservation, De-Extinction and the Precarious Future of Wild Things.” Follow her on Twitter @TheOChronicle.

Source: Vice

To help sustain this work become a paid monthly subscriber at $12 per month. Your support is much appreciated. Thank you.

Subscribe to our Ezili youtube channel

Thank you for your donation to support the Hurricane Matthew victims with Zili Dlo Clean Water Renewable Power

***

Donate to Support Hurricane Matthew Victims

Add a comment:

Powered by Facebook Comments