The Cost of Liberation: A Conversation with Prof. Marlene Daut on her book – “The First and Last King of Haiti – The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe”

Key Èzili Dantò FreeHaytiMovement Discussion Topics

Daut’s book (p. 205) cites The Political and Commercial Gazette of Haiti, the state-run newspaper under Dessalines, which reported:

“When under interrogation she claimed to know nothing about the 300,000 pounds that the French accused Toussaint of having hidden somewhere in Saint-Domingue, the French subjected her to ‘instruments of torture… while in a state of pregnancy… which resulted in a premature labor,’ causing the baby to be stillborn.”

How did Suzanne Louverture become pregnant at 60 years old and suffer a stillbirth while being tortured by the French? Who impregnated her? Was she raped by the French as torture methods? Or, was the baby she lost in captivity Toussaint’s child?

Who were Baron de Joseph Dessalines (Daut, p. 418) and Baron de Dessalines (Daut, p. 456, referred to as Dessalines’s son) in Christophe’s Kingdom? What was their relationship to Emperor Dessalines when he was alive? If they were his sons, who were their mothers?

Given that Pétion, Gérin, and Boyer orchestrated Emperor Dessalines’s assassination, why would King Henry Christophe send Dessalines’s son—Baron de Dessalines—on a diplomatic mission to Boyer’s South in 1818 to propose unifying the North and South under the Kingdom after Pétion’s death (Daut, p. 456)? Wouldn’t that have been politically unwise or diplomatically provocative?

Lastly, what can you tell us about Rosillesse and Marie Jeanne Dessalines, who lived with Marie-Claire Heureuse Dessalines in Okap on the same street as Marie Bunel in 1803 (Daut, p. 444)?

In his Political Gazette, Christophe himself admitted to being part of the Pétion/Gérin/Férou plot to kill Dessalines, a revelation that raises questions about his cunning motivations and justifications (Daut, p. 317-321).

Recall how Leclerc attempted “to convince Dessalines to eliminate the “men of color,” which is to say the people of mixed race, Dessalines underscored that “the execution of that atrocious project” was “proposed to me without any embarrassment, and had already been begun by the French.” (Daut, p 200)

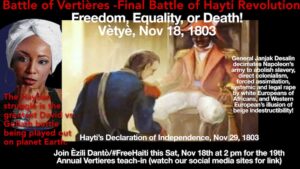

Join us for this deep dive into Hayti’s revolutionary history and its modern implications!

Where Black Majority Peoples in Kingdom & Story?Afrikan-Born in Henry Court?

People of Color2identify Black Hayti ProblematicHaytian majority not colore

Add a comment:

Powered by Facebook Comments